Table of Contents

Carbon fiber is often treated as a default “upgrade material.”

In many OEM projects, once performance targets become aggressive or products move upmarket, carbon fiber is quickly placed on the table as an assumed solution.

From an engineering standpoint, however, carbon fiber is not always the correct choice.

The real question OEM teams should ask is not:

“Can we use carbon fiber?”

but rather:

“Does carbon fiber solve a real engineering problem in this product?”

This article provides an engineering-based framework to help OEM brands determine when carbon fiber truly adds value—and when it introduces unnecessary cost, risk, and complexity.

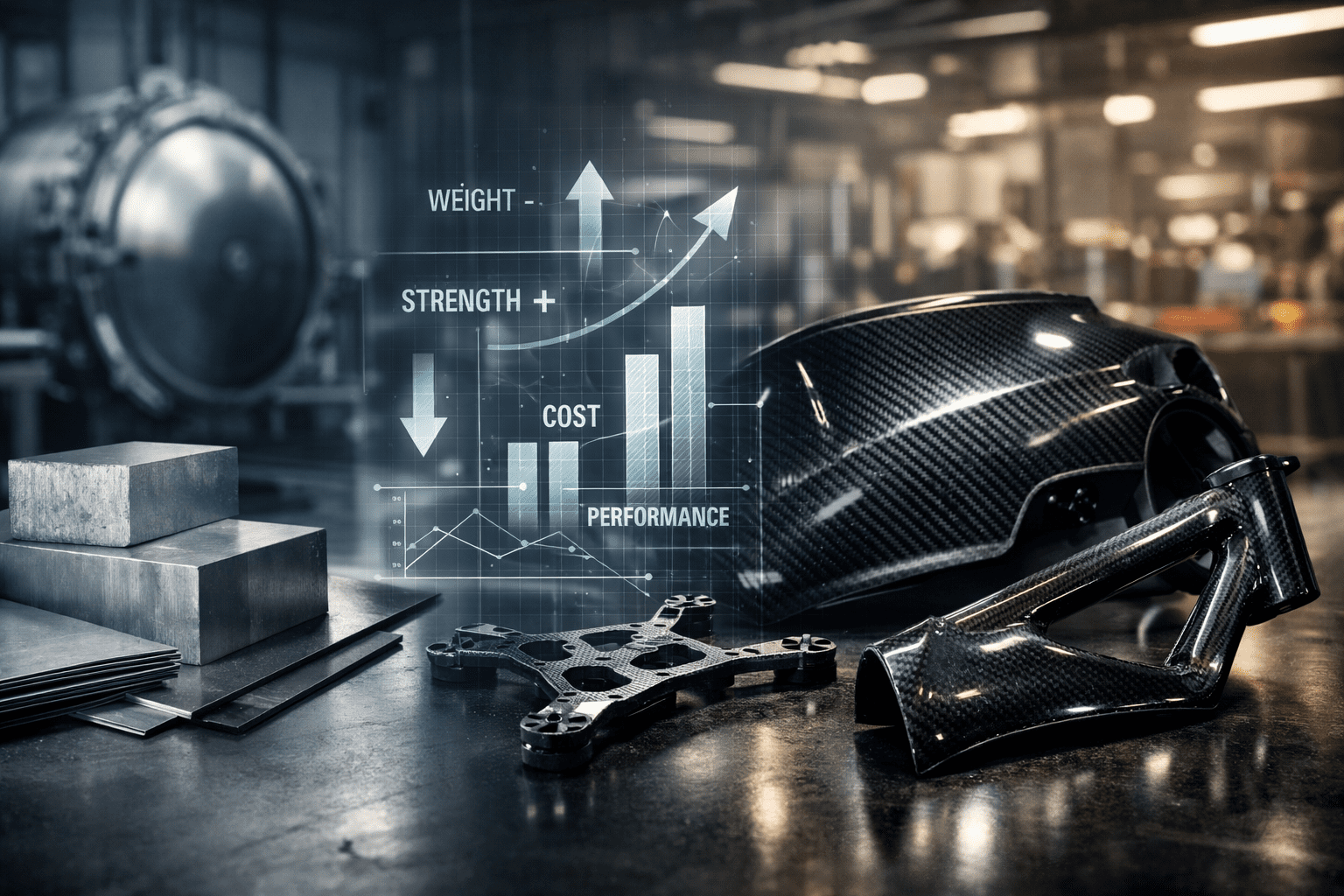

Understanding Carbon Fiber as an Engineering Material

carbon fiber vs metal engineering

Carbon fiber is fundamentally different from metals and plastics.

It is:

- Anisotropic – strength depends on fiber orientation

- Structure-driven – performance comes from layup logic, not thickness

- Process-sensitive – manufacturing method directly affects quality and consistency

Because of this, carbon fiber performs best only when the design is intentionally engineered around its characteristics.

Using carbon fiber as a drop-in replacement for metal or plastic often leads to disappointing results.

When Carbon Fiber Is the Right Choice

Carbon fiber becomes the right solution when it directly addresses a clear engineering objective.

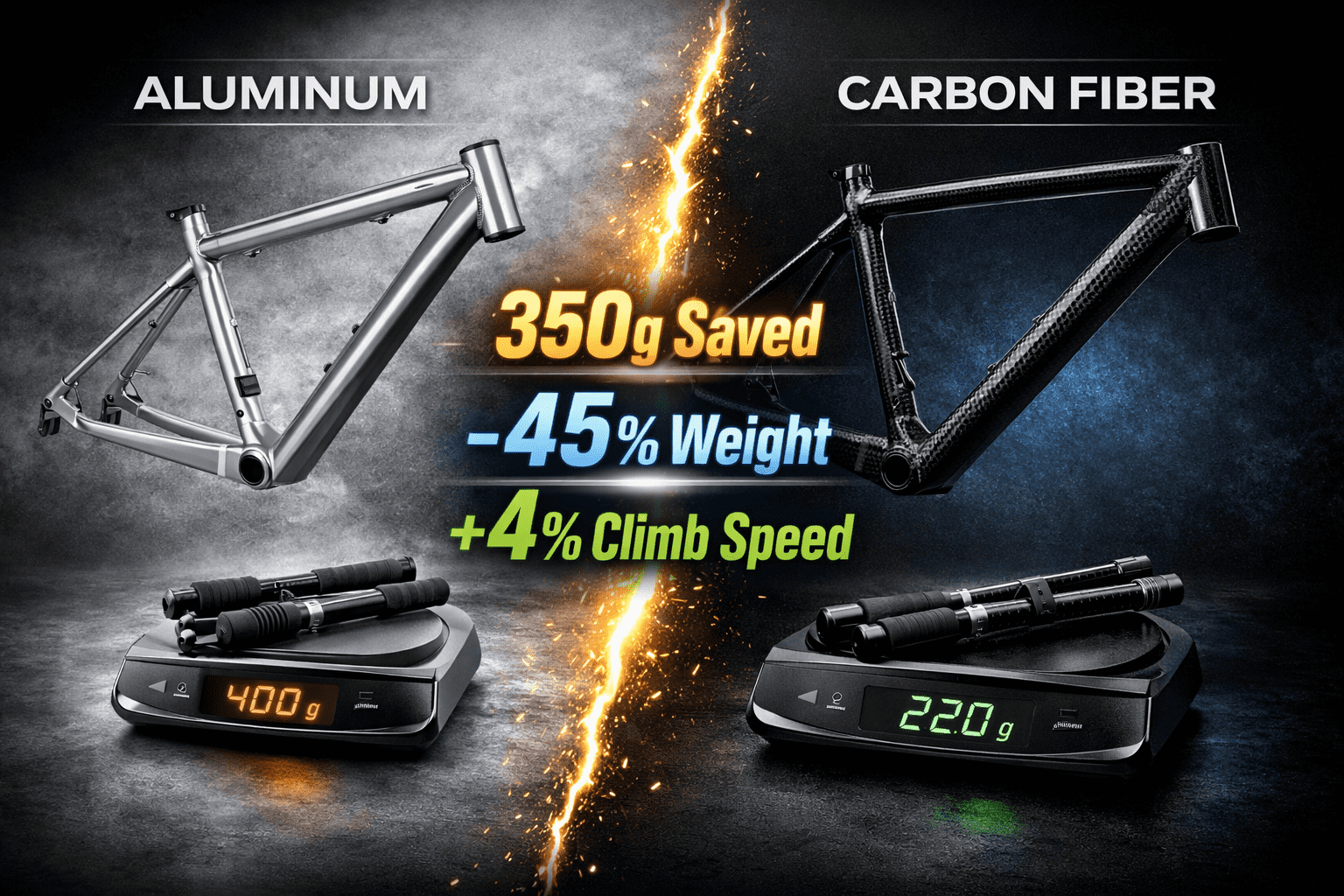

1. Weight Reduction Directly Improves System Performance

Carbon fiber excels when weight reduction delivers measurable system-level benefits, such as:

- Increased driving range in electric vehicles

- Improved acceleration and handling

- Reduced fatigue in mobility or wearable products

- Lower inertia in UAV or high-speed components

If reducing mass changes how the entire system performs—not just the part itself—carbon fiber often justifies its cost.

2. High Stiffness-to-Weight Ratio Is Required

In applications where stiffness matters more than raw strength, carbon fiber offers advantages that metals struggle to match.

Typical scenarios include:

- Large panels requiring minimal deflection

- Structural skins where thickness must be controlled

- Long-span components sensitive to vibration

Carbon fiber allows engineers to place stiffness exactly where it is needed, rather than adding material uniformly.

3. Complex Geometry Benefits from Directional Strength Tuning

Carbon fiber is uniquely suited for complex shapes where load paths are non-uniform.

Through fiber orientation control, engineers can:

- Reinforce high-stress regions

- Reduce material in low-load zones

- Tune torsional, bending, and shear behavior independently

This level of control is impossible with isotropic materials.

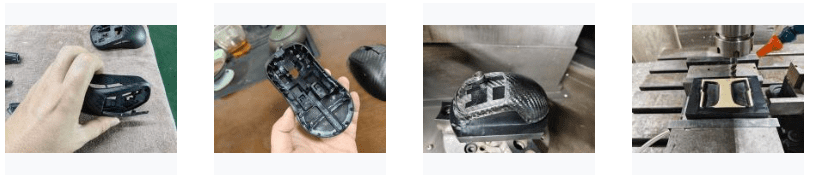

4. Premium Surface Quality Adds Brand Value

In some products, surface quality is not just cosmetic—it is part of the brand identity.

Carbon fiber can deliver:

- Seamless Class-A surfaces

- Integrated structure and appearance

- A premium tactile and visual feel

When appearance and structure can be combined into a single part, carbon fiber can reduce part count and assembly complexity.

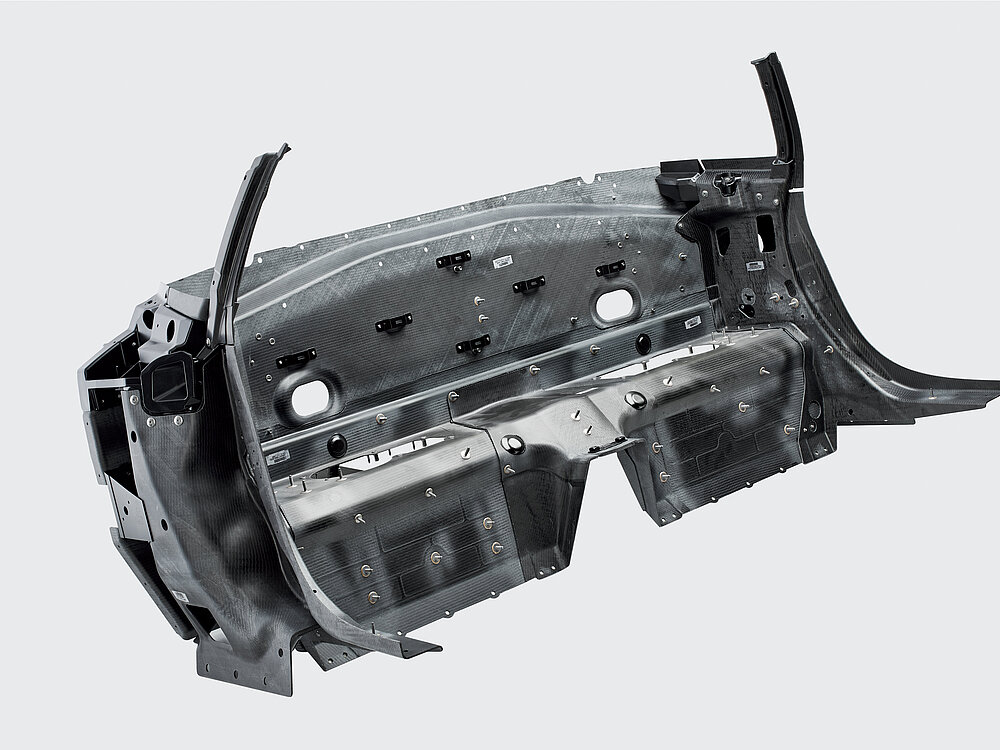

5. Structural Integration Reduces Overall Complexity

Carbon fiber enables multi-function integration, such as:

- Structure + enclosure

- Reinforcement + mounting interface

- Stiffener + aesthetic surface

When a single carbon fiber component replaces multiple metal or plastic parts, the system-level ROI often becomes compelling.

When Carbon Fiber Is the Wrong Tool

Despite its advantages, carbon fiber is frequently misapplied.

1. Cost Sensitivity Outweighs Performance Gain

If the product:

- Competes primarily on price

- Has minimal performance differentiation

- Does not benefit from weight reduction

carbon fiber rarely makes economic sense.

In these cases, optimized aluminum, steel, or reinforced plastics often deliver better ROI.

2. The Part Is Purely Cosmetic

Using carbon fiber solely for appearance—without structural intent—often leads to:

- High cost with limited functional benefit

- Over-engineered solutions

- Customer pushback on pricing

If the only goal is “carbon look,” alternative materials or surface technologies may be more appropriate.

🔘 Get Your Aerodynamic Upgrade Plan

3. Unrealistic Tolerance Expectations

Carbon fiber manufacturing has realistic tolerance limits.

If a part requires:

- Extremely tight dimensional control across large surfaces

- Precision mating without inserts or secondary operations

carbon fiber may introduce unnecessary risk unless the design accommodates composite realities.

4. Design Is Unstable or Continuously Changing

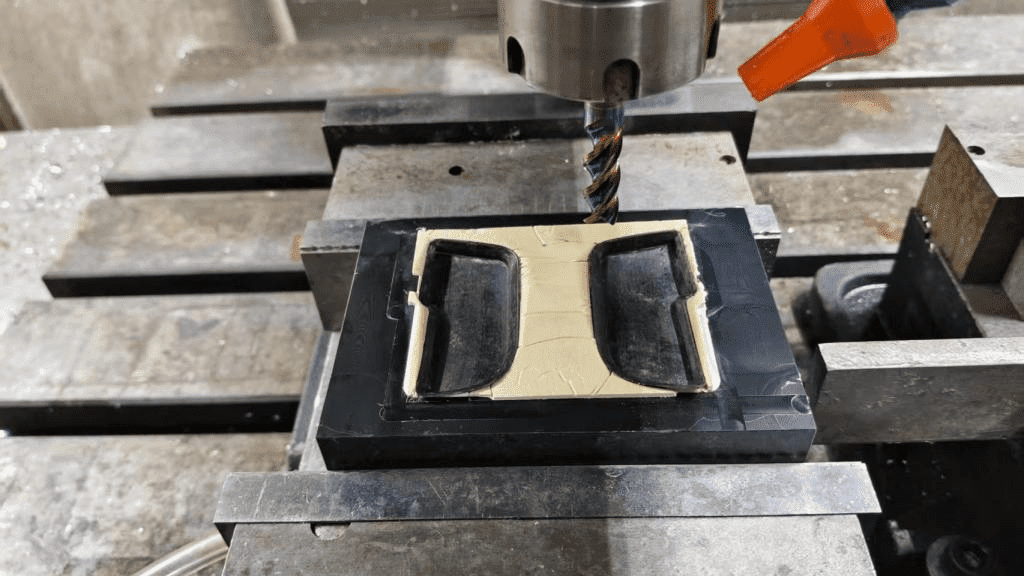

Carbon fiber development relies heavily on:

- Tooling

- Process definition

- Layup validation

When designs change frequently, carbon fiber becomes inefficient and costly compared to flexible manufacturing methods like machining or injection molding.

5. Extremely Low Volume with No Scale Roadmap

For one-off or ultra-low-volume parts with no future scale:

- Tooling costs dominate

- Process optimization is never recovered

Carbon fiber shines when there is a clear path from prototype to production, even at modest volumes.

🔘 Get Your Personalized Quote Now

Engineering Takeaway: Carbon Fiber Is a Strategy, Not a Shortcut

Carbon fiber delivers exceptional value only when engineering intent is clear.

It performs best when:

- The problem is well-defined

- The structure is designed for the material

- Manufacturing is considered from the start

Without this clarity, carbon fiber becomes:

- An expensive material choice

- A source of avoidable risk

- A poor substitute for better-engineered alternatives

For OEM brands, the most successful carbon fiber programs are not driven by trend or aesthetics—but by engineering logic and system-level thinking.

Final Thought for OEM Decision Makers

Before choosing carbon fiber, ask:

- What engineering problem are we solving?

- What system benefit does weight reduction deliver?

- Is the design stable enough to justify composite tooling?

If these questions have clear answers, carbon fiber can be transformative.

If not, the smartest engineering decision may be not to use it at all.

Q1: Is carbon fiber always better than aluminum or steel?

No. Carbon fiber outperforms metals only when weight reduction, stiffness tuning, or structural integration delivers clear system-level benefits. Without these advantages, metals often provide better cost-to-performance ratios.

Q2: When does carbon fiber make the most engineering sense?

Carbon fiber is most effective when reducing weight directly improves performance, such as range, handling, fatigue reduction, or structural efficiency—especially in mobility, UAV, and high-performance products.

Q3: When should OEMs avoid using carbon fiber?

OEMs should avoid carbon fiber when the design is unstable, volumes are extremely low with no scaling plan, tolerances are unrealistically tight, or when carbon fiber is used only for cosmetic reasons.

Q4: Can carbon fiber replace metal parts directly without redesign?

In most cases, no. Carbon fiber requires structural redesign, fiber orientation planning, and DFM optimization. Simply copying metal geometry often leads to poor performance and high cost.

Q5: Is carbon fiber suitable for low-volume production?

Carbon fiber can support low-to-mid volume programs when there is a clear roadmap toward scale. For true one-off parts with no future volume, tooling costs often outweigh the benefits.

Q6: How should OEM teams decide whether carbon fiber is worth the cost?

OEM teams should evaluate carbon fiber based on system-level impact—performance gain, part integration, assembly reduction, and long-term scalability—not material price alone.